Every year, around 25,000 people attempt the climb to the summit of Africa’s highest mountain, Kilimanjaro. Thousands never make it, beaten back by a combination of altitude sickness and exhaustion. Few do it carrying a month’s worth of stoma bags and rehydration tablets. But then, there aren’t many people like Glen Neilson.

Despite his insistence that he’s just a regular guy, Glen has been climbing mountains for over 25 years. Long before he ever put on a pair of climbing boots and threw a rucksack over his shoulder.

As Glen puts it “When you’ve overcome a near-death experience and having to go to the toilet fifty times a day, walking up a mountain is no big thing!”

Except, it is a big thing. A very big thing. Standing 16,893ft above sea level, its peak is permanently encrusted in snow and ice. Giving it the local nickname Kibo.

So how did it happen that a man who started his career under the sea as a Royal Naval submariner, came to love life in the clouds? For the answer to that, we have to go back to 1988.

“I’ve always loved adventure. As soon as I left school, I wanted to escape the classroom and see the world. So I joined the Royal Navy and by my early twenties, I was living the dream on-board a nuclear submarine. I then fell ill and had to be airlifted to hospital where I was told I had Thyroid Cancer. Luckily, they caught it early.

I then got Ulcerative Colitis and while I tried to remain happy-go-lucky, it wasn’t easy having to use the toilet 40-50 times every day.

I think this is why I now look at my stoma as a life saver, not a life limiter. Me and the little sh*t (as I affectionately call my stoma) didn’t get off to the best of starts though - on my first holiday abroad, I caught MRSA and spent 8 long months recovering at home with a hole in my stomach!”

As a climber, you’re told to look up and ahead, rather than down and back. It’s good advice and it’s exactly how Glen tries to live his life.

Since having a stoma and finding the right bag, he’s owned several successful businesses, volunteered to help other people with stomas, partnered with ConvaTec and got into hiking, in a big way. But as Glen explains “I’ve always had itchy feet!. So when the opportunity came to walk Kilimanjaro and raise money for Colitis research, I had to go for it.”

In the months before Glen embarked on the expedition, he stepped up his training, walking up both Ben Nevis and Snowden, while regularly taking off on 20+ mile hikes. But how do you prepare for the hardest part of the climb - the altitude sickness? You can’t.

When most people think of Kilimanjaro, they actually picture something more akin to the Antarctic. Walking through miles of snow and ice. In reality, the mountain’s environment is one of extremes. A place where rainforests exist alongside deserts and snow-capped peaks.

This was going to be a bit trickier than packing for two weeks in Lanzarote. But as Glen explains, that wasn’t the hardest part. “I hadn’t realised it, but Tanzania has a strict policy banning all single use plastics, which I fully support, except that would include my stoma bags. Luckily for me, awareness of stomas is really low out there and I knew that if I needed to, I could tell the customs official that they were reusable.”

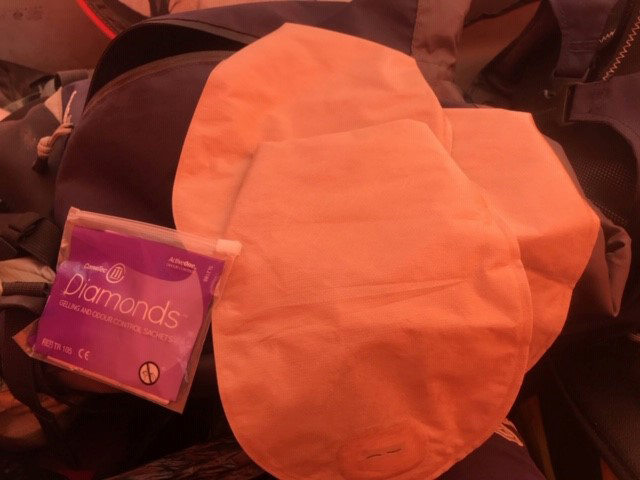

“I’d read that the best things to wear were lots of layers that you can just add and remove. I’d be walking and sleeping in temperatures up to minus 25 degrees. Plus, unlike everyone else on the trip, I had to pack for the little sh*t. He needed a month’s worth of stoma bags. I chose ConvaTec’s Mouldable Esteem+ two-piece bag. I had full confidence that it would stick to my body in all temperatures and in the freezing temperatures, I could leave the baseplate in place for days at a time. I also packed Diamonds crystals (amazing things when you need to solidify fast!), gaffa tape (just in case) plus 25 packs of Dioralytes.”

The entire expedition takes eight days in total, six days going up and two days coming back down. For the climb to base camp, Glen and the nine-strong group were supported by 28 porters and four expert guides.

Glen says that base camp was a lot more well-equipped than he had imagined. “The porters set up everyone’s tents, plus a communications centre, mini hospital, kitchen and dining area. I was humbled how well we were treated and amazed at the food these guys prepared. I was expecting basic rations, not two-course meals!”

The group were to begin their ascent at 11pm, avoiding the baking hot UV rays. The porters would stay at camp, leaving Glen, the team and four guides to climb the remaining part of the ascent alone – carrying their own bags plus the minimum recommended five litres of water.

And if, like us, you’re wondering what you eat just before you’re about to walk up a mountain, Glen says “a nice big, hot bowl of porridge.”

Weighed down by multiple layers of clothes, a thick coat and a rucksack containing stoma bags, accessories, waterproofs, fives litres of water and factor 50 sunscreen block, Glen set off with the rest of the group, walking through the night to reach their first milestone.

Temperatures at night can drop to minus 25 degrees and it didn’t take long for Glen to know what that felt like. Glen explains “We’d been walking for about three hours when I decided to check my bag. My hands were freezing and I couldn’t get them warm again. I can smile about it now but at the time it was really scary – I couldn’t even undo the zip on my boot bag.”

“People are always amazed when I tell them that to get to the top you have to walk through a rainforest! It’s like a proper misty jungle that covers the lowlands of the mountain to around nine thousand feet. The rain was torrential and I’m not joking when I say it nearly washed away our tents.” Still, if there’s one thing we Brits know all about, it’s rain. Altitude sickness on the other hand…

The two words that strike terror into every climber. For Glen, the biggest fear wasn’t the symptoms, it was getting removed from the mountain.

As he says “altitude sickness is caused by a lack of oxygen and can be a silent killer, so the guides don’t take any chances. The moment anyone starts showing serious symptoms, they’ll be evacuated from the mountain. I actually was suffering but through my own ignorance, I didn’t think anything of it.

I was having terrifying dreams about being strangled. It was only much later that I discovered this is a classic sign of something called High Altitude Pulmonary Oedema. I know it’s selfish, but even if I had of known, my desire to reach the summit would have meant I’d have never told a soul.”

One of the things you probably wouldn’t expect to come home with after a trip to Kilimanjaro is a suntan. But through its height and proximity to the Equator, its UV rays are extremely powerful. Or as Glen puts it “like putting your head inside an oven. I can honestly say that the heat was on another level – it’s the fiercest heat I’ve ever felt. And the blinding glare could cause a headache through even the thickest wrap-around sunglasses.”

“I never think too much about having a stoma. I’m lucky because I’ve found a great product which means I often forget I’m wearing one. But because I was being supported by ConvaTec and raising funds for Colitis UK, I’d agreed to keep a journal of my stoma experiences. Being honest, having a stoma had advantages and disadvantages.

As you can imagine, toilet facilities are pretty basic, just a wooden hut over a hole in the ground. It always made me both wince and laugh listening to the other guys going to the toilet at night in the freezing cold and rain! On the flip side, I had to carry my used stoma bags with me, since no rubbish can be left on the mountain. I also suffered my worst stoma fear – diarrhea, which thankfully was fairly short-lived.

There’s no doubt that the biggest challenge for me was dehydration. I was drinking over five litres of water every day and was barely needing to urinate. I was going through my Dioralytes like a hot knife through butter. The 25 packs I thought I’d over-packed would only just be enough.”

Glen and the rest of the team reached the summit on day seven. So how did it feel?

“At first it was sheer relief. About an hour earlier we had sunk to our knees on being told that we’d reached the false summit and would still have to walk around the rim to reach the top! When I eventually did reach the pinnacle and planted the ConvaTec flag, it was a tremendous feeling of pride.”

Which as Glen explained, was very quickly followed by an overwhelming desire to get down as quickly as possible. “By now we were all suffering from headaches, sickness and shortage of breath, so far from being able to enjoy our accomplishment, we all just wanted to get back to base camp. In total we only spent around 20 minutes at the summit enjoying the most amazing views out across Africa. If I’d have known what was to come, I might have hung around for longer.”

What goes up must come down. And although the descent was only going to take a third of the time compared to the ascent, Glen says it was the hardest two days of his life.

“I always prefer going up mountains, but what made this so difficult was the conditions underfoot, with loose shale and rocks making every step hazardous. It didn’t help that our water supplies had frozen at the summit, so not only were we carrying solid blocks of ice down, but we couldn’t get a drink for the first four to five hours. We actually walked for 15 hours straight on the last day, which tells you how desperate we were to get home!”

In total, Glen raised £2,900 for Colitis research, smashing his initial £500 target. He overcame personal challenges and proved once again that having a stoma is no barrier to leading a full and adventurous life. So, would he do it again? We’ll leave the final words to Glen:

“No way man!”